EU enters race with the US to produce clean tech in bid to reduce reliance on China

The European Union presented its Critical Raw Materials Act this week, in an attempt to secure supply chains and boost European autonomy to ensure the EU has access to materials needed to meet the bloc’s target of moving to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050

Key targets

The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act is one of the cornerstones of the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan, together with the Net-Zero Industry Act, which sets a target for the EU to produce 40% of its own clean tech by 2030, such as solar power or fuel cells, partly by streamlining the granting of permits for green projects. The bloc also announced a goal for carbon capture of 50 million tonnes by 2030.

Metals, including lithium, copper and nickel are vital in green technology. The EU proposed classifying copper and nickel as critical raw materials, as neither of them were included in the EU’s last list of critical raw materials published in 2020.

The shift to clean energy is set to drive a huge rise in the requirements for these materials. Demand for critical raw materials is expected to skyrocket by 500% by 2050, according to the World Bank.

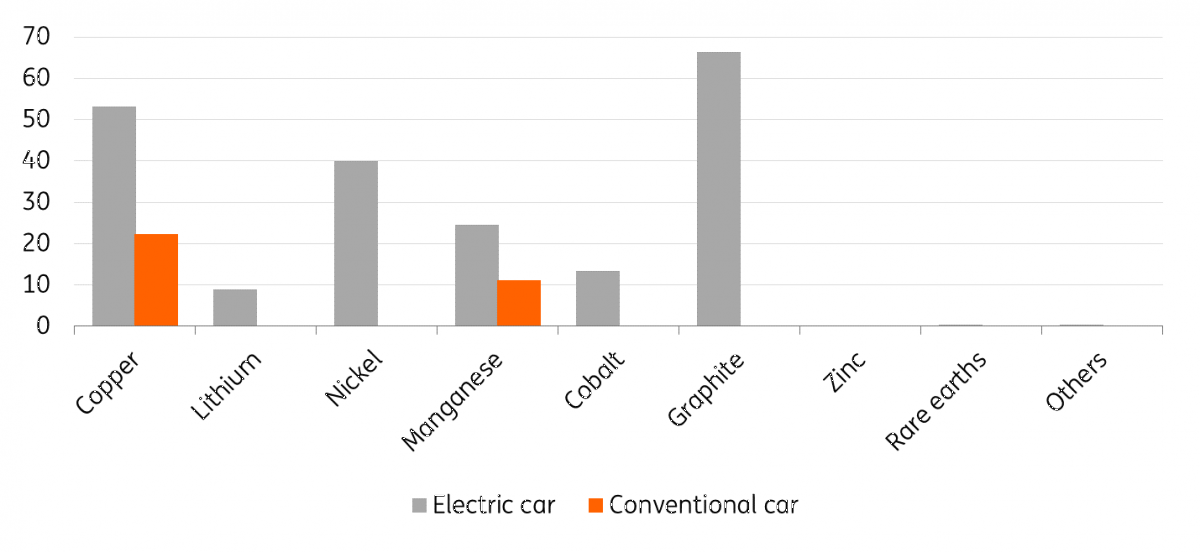

Solar photovoltaic plants, wind farms and electric vehicles (EVs) generally require more critical minerals to build than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. A typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an offshore wind plant requires 13 times more mineral resources than a similarly-sized gas-fired plant.

Europe is responsible for more than one-quarter of global EV assembly, but it is home to very little of the supply chain apart from cobalt processing at 20%, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Global investment in the green energy transition is set to triple by 2030 from $1 trillion last year, the EU said. The bloc will need €400bn of investment a year to decarbonise and meet its target of net-zero emissions by 2050, it estimated.

Without a safe and sustainable supply of critical raw materials, there will be no green and industrial transition.

(Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President for A Europe Fit for the Digital Age)

As part of the Critical Raw Materials Act, the EU has set targets for the region to mine 10% of the critical raw materials it consumes, like lithium, cobalt, and rare earths, with recycling adding a further 15%, and increased processing to 40% of its needs by 2030.

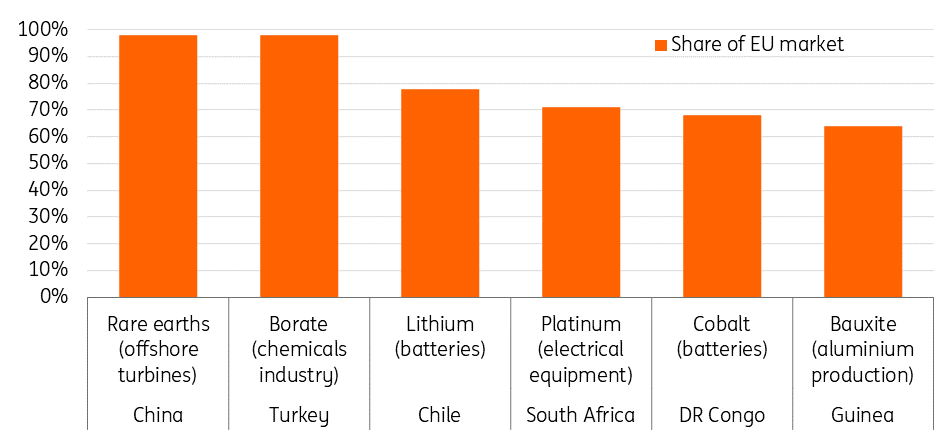

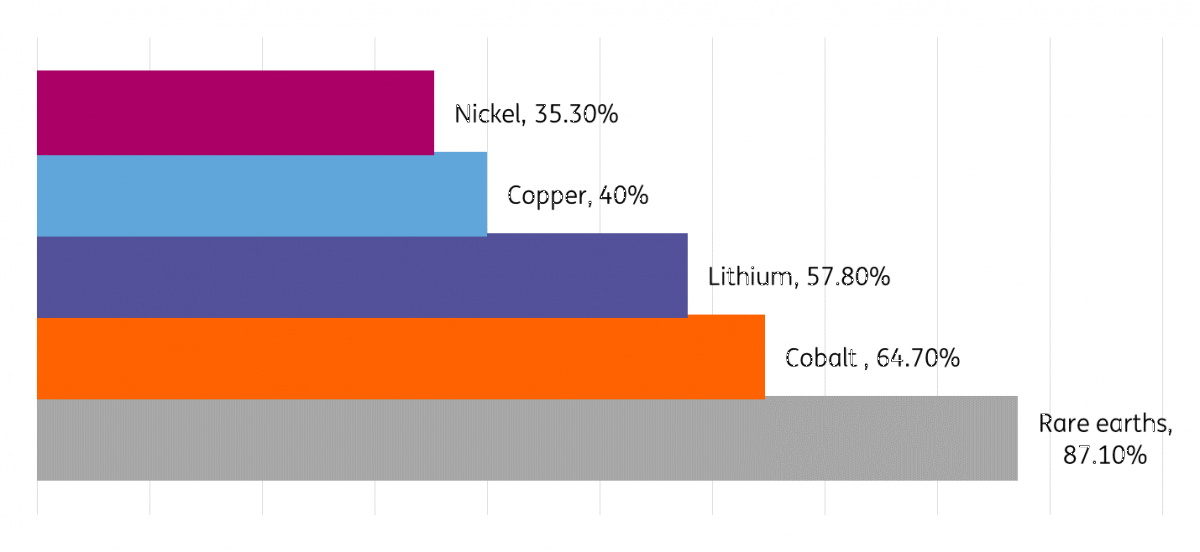

Today, China processes almost 90% of rare earths and 60% of lithium. The EU said that no more than 65% of any key raw material should come from a single third country. The EU is almost entirely dependent on imports of these raw materials, particularly from China with 100% of the rare earths used for permanent magnets globally refined in China and 97% of the EU’s magnesium supply sourced from China.

In 2021, magnesium prices skyrocketed amid supply shortages after China’s production curbs to limit power consumption. The shortage of magnesium in China threatened European industry, including the automotive, construction and packaging sectors. Magnesium is an essential raw material for the production of aluminium alloys, which account for about 50% of the total magnesium consumption.

This has shown how a power crisis in China can trigger a magnesium shortage in Europe which can cause a shortage of aluminium in Europe, which in turn can hit European car production. The risk of depending on Chinese imports is what the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act is trying to avoid by strengthening the bloc’s raw materials strategy.

European companies used to produce magnesium, but they closed down because of competition from cheap imports from China. Meanwhile, 63% of the world’s cobalt, used in batteries, is extracted in the Democratic Republic of Congo, while 60% is refined in China.

EU demand for lithium batteries, which power electric vehicles and energy storage, is set to increase 12 times by 2030 and 21 times by 2050, while the bloc’s demand for rare earth metals, used in wind turbines and EVs, is set to rise five to six times by 2030 and six to seven times by 2050.

The EU would recognise firm plans to mine or process raw materials as "strategic projects", which could benefit from shorter permitting timeframes, 24 months for extraction permits and 12 months for processing and recycling permits, and access to financing. Currently, it can take between two and seven years to build a new factory, depending on the technology and member state. It takes 10 years on average until a new mine comes online.

Europe has only one operational lithium mine, in Portugal, producing low-grade ore, which is not suitable for use in battery production.

Last year, a French minerals company unveiled a lithium mining project, containing one million tonnes of lithium – enough for the extraction of 34,000 tonnes per year for 25 years. The new mine will be operational by 2028.

Europe’s largest known deposit of rare earth minerals was discovered in Sweden’s Arctic this year, but it will take 10-15 years before mining can begin.

Under the Act, Member States will also have to develop national programmes for exploring geological resources.

Soaring EV battery demand will require 50 new lithium projects, 60 nickel mines and 17 cobalt developments by 2030 to meet global net carbon emissions goals, according to the IEA, assuming an average annual mine production capacity of 8,000 tonnes for lithium, 38,000 tonnes for nickel and 7,000 tonnes for cobalt.

The EU acknowledged that it will never be self-sufficient in supplying raw materials and will continue to rely on imports for most of its consumption. In trade, the EU would seek to expand its network of raw materials partnerships and free trade agreements and establish a Critical Raw Materials Club.

Supply of critical raw materials to the EU is often every concentrated

Selected countries by share of total EU mineral supply (%)

Battery supply chains revolve around China

Critical raw materials, like lithium, cobalt and rare earths, are essential for manufacturing green technologies, including batteries, wind turbines and solar panels. A lack of investment in mining has resulted in supply shortages and rising prices.

Although the domestic production of certain critical raw materials exists in the EU, notably hafnium, in most cases the EU is dependent on imports from non-EU countries.

The rapid increase in EV sales during the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated concerns about China’s dominance of lithium battery supply chains. Meanwhile, Russia’s war in Ukraine has pushed prices of raw materials, including cobalt, lithium, and nickel to record highs.

The risks associated with the concentration of production are in many cases heightened by low substitution and low recycling rates. For example, in EV batteries, there is no substitute for lithium.

More than 80% of the world’s lithium is mined in Australia, Chile and China, which also controls more than half of the world’s processing and refining.

Chinese companies have also made significant investments in projects overseas, in Australia, Chile, the DRC and Indonesia. In Chile, the second biggest lithium producer after Australia, only two companies produce lithium – US-based Albermarle Corp. and local firm SQM, in which China’s Tianqi Lithium Corp. has more than 20% stake. They mainly make lithium carbonate – 90% of which goes to Asia.

China dominates many elements of the downstream EV battery supply chain, from material processing to the construction of cell and battery components. China only accounted for about 15% of global lithium raw material in 2022 but around 60% of the battery metal is refined there into specialist battery chemicals. China also produces three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries. This is a result of Beijing’s early push towards electrification, particularly through subsidising EVs.

China controls the processing of key energy transition metals

Share of global processing of selected raw materials that take place in China (%)

Minerals used in electric cars compared to conventional cars

Europe’s answer to the US Inflation Reduction Act

The EU’s regulation is part of Europe’s answer to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which offers $369bn of subsidies to green tech manufacturers and has prompted several multibillion-dollar investments into US battery manufacturing. Meanwhile, the EU’s green deal lacks clarity on funding.

The IRA provides tax credit incentives to both EV producers and consumers in the US if the car’s battery is made with raw materials and components that are sourced within the US, or from one of the country’s free trade partners.

In January, General Motors announced it would invest $650m in Lithium Americas – the largest such deal to date in the US. The deal will give the automaker exclusive access to the first phase of lithium carbonate output at the Thacker Pass project in Nevada.

Some EU leaders have criticised the IRA, arguing it discriminates against European companies selling to the US. With US energy costs up to four times lower than in Europe, it provides incentives for European manufacturers to move production to the US.

Earlier this week, Europe’s largest car manufacturer by volume, Volkswagen, said it planned to increase investment in China and build EV factories in the US and Canada. The German carmaker will build its first plant outside of Europe after it had told EU officials that it was putting on hold a planned battery plant in eastern Europe while it waited for the bloc to respond to the US package of green incentives. The carmaker estimated it could receive $10bn in subsidies and tax breaks over five years.

Countries accounting for the largest share of EU supply of CRMs

2023 Critical Raw Materials (new as compared to 2020 in bold)

Next steps

The proposed regulation will be discussed and agreed by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, a process that is set to take a few months, before its adoption and entry into force.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more