How electric cars will move from niche to disruptor

Industrial-scale production is the coming gamechanger

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Is net zero by 2050 at risk?

-

The Edge

Can emissions taxes decarbonise the LNG industry?

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

The Edge

Can carbon offsets deliver for oil and gas companies?

-

Featured

Wood Mackenzie 2023 Research Excellence Awards

-

The Edge

Nuclear’s massive net zero growth opportunity

Electric vehicles sales shot the lights out in 2021, surpassing all expectations. Is this the long-awaited sign of accelerating disruption in transportation? I asked Ram Chandrasekaran, Principal Analyst, Transportation for his latest thoughts.

What happened in 2021?

EV sales were 6.5 million, more than double the previous year’s, and well above our forecast of just under 5 million. EVs’ 9% share of global light vehicle sales in 2021 is the first substantive challenge to 100 years of dominance by ICE vehicles. China and Europe accounted for 84% of sales with subsidies a big factor, while the global shortage of silicon chips that dragged down ICE vehicle supply affected EV sales much less.

China has managed to add low-end models that have pulled in young, first-time buyers.

Who is buying EVs?

It varies. In Europe and North America, it’s mainly niche consumer segments – the ‘affluent innovators’ or ‘early technology adopters’. China has managed to add low-end models that have pulled in young, first-time buyers. We’re still in the very early stages of market development, with EVs just 1.3% of the global vehicle stock.

Which are the leading automakers?

The biggest seller in 2021 was Tesla with almost 1 million cars, one in every six EVs sold globally. GM Group was second with its Wuling Mini model the biggest seller in China; VW was third, led by the ID3 Hatchback; and BYD, the Chinese car and battery manufacturer backed by Warren Buffet, fourth.

The entire industry, though, is repositioning for the big shift to EVs. The biggest players are preparing a global product offering to suit different markets and different segments. We think those best positioned at this point for the mass rollout include VW, Hyundai Kia, Ford (with its three flagships, the Mustang, Transit and F150, all available in electric by the end of 2022) and GM (the Chevy Equinox).

The biggest players are preparing a global product offering to suit different markets and different segments.

When will EVs be competitive?

They already are in some niches and will break into many more segments over the next three to four years. A generalised cost comparison isn’t straightforward. Our modelling suggests EVs beat ICE cars on lifetime costs over 10 years, depending on how future gasoline prices develop. But EVs’ purchase price is usually higher, and that puts off many customers.

The coming gamechanger is the imminent industrialisation of EV manufacturing. Investment underway by traditional automakers will lead to a massive scaling up of production volumes over the next few years and significantly lower unit costs, which will close the price gap.

The battery is around one-third of an EV’s total cost. Battery costs have already fallen by an order of magnitude and should continue to decline over time. However, soaring lithium prices may mean 2022 is the first year in a decade battery costs don’t fall – EVs’ competitiveness remains hostage to battery raw materials markets.

Broader government, state and city policy initiatives are also ramping up to support EVs.

Is there enough policy support?

Subsidies clearly make a big difference and will continue to be needed until purchase prices come down. China’s sales doubled last year after subsidies that ended in 2019 were re-instated; these now form part of China’s green stimulus. Europe’s subsidies (up to EUR9,000/EV in Germany, France and the UK) save 20% to 25% on a VW ID3 hatchback, making it price-competitive with the ICE equivalent. Another fillip for EVs could come from the EU’s ‘Fit for 55’ proposals which aim to tighten already demanding emissions standards for passenger cars.

The US has lagged on incentives, but EVs will get a big boost if the Biden administration’s proposed new fuel economy targets go through. These include 8% a year incremental fuel-saving targets for new light-duty vehicles.

Broader government, state and city policy initiatives are also ramping up to support EVs. Countries representing over 50% of global car sales have expressed an intent to phase out ICE sales. Numerous cities and towns have already restricted access to high pollution vehicles and will inevitably expand to cover all emitting vehicles. EVs will also be central to the nationally determined contributions (NDCs), due to be submitted before COP27 in November – notably in Europe and the US, where emissions from transportation are around 30%, double the global average.

So, what is the outlook for EVs?

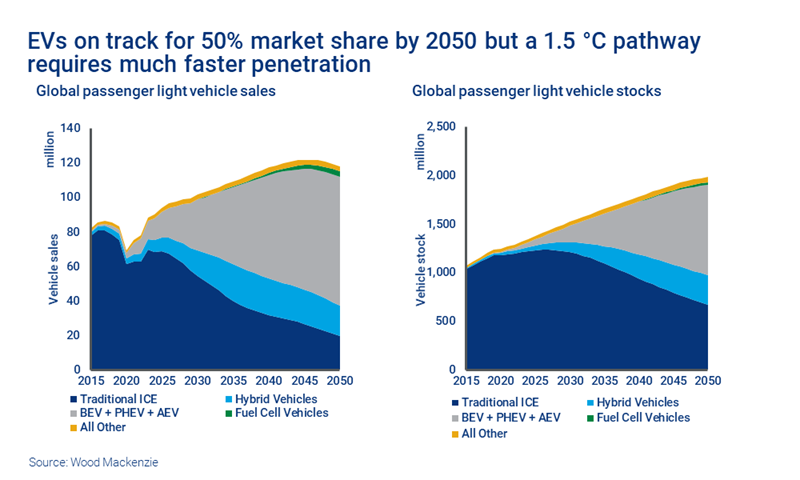

Very bullish – we are at the beginning of a transport revolution. Supportive policy changes, automakers’ increased commitment to long-term investment and shifting sentiment among consumers led us to increase our 2050 projection for EVs in our November 2021 base case by a whopping 20%, to 950 million. That’s aligned with a 2.3 °C to 2.5 °C pathway.

We expect EV sales to double by 2025 and double again to reach 30 million globally by 2030. Annual EV sales eclipse ICE cars by 2029 in China, 2030 in Europe with North America following later in the decade. Yet by 2030 EVs will still only be around 11% of the global car stock – the typical 10-year turnover of the car fleet presents a stiff headwind to EVs’ hegemony.

Even with declining ICE car sales, the rapid growth of EVs we project is nowhere near fast enough to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. To get the world on a 1.5 °C pathway, sales need to grow twice as fast to reach 70 million a year by 2030, leading to a global stock of 1.5 billion by 2050 (83%).

That’s only going to happen if policy is sufficiently aggressive in the three biggest markets, automakers deliver industrial-scale manufacturing and the consumer can be convinced of EVs’ value proposition for their personal mobility.